Queer & Filipinx: Unlearning Anti-Blackness In My Own Communities

My younger, queer and Filipinx self would sit at the kitchen table while my parents, lolas, and lolos would tell me about their immigration stories: their individual resiliency in pursuit of the American dream from Cebu to San Francisco. They left their families and friends behind, had to put in hours of hard labor, and faced discrimination for me to be here today. I always felt indebted to my elders for their work, which made it hard for me to come out to them given our conservative Catholic Filipinx culture.

Without an ability to speak to my Filipinx elders about my queer identity, I resorted to finding information on what it meant to be queer through whatever was on TV. Ellen Degeneres, Chris Colfer, and white cisgender queer folx were positioned as the model of queerness, setting a precedent that whitness was the apex of the LGBTQIA+ community and that I as a person of color didn’t belong.

What this upbringing failed to educate me on was the crucial roles Black folx have played in both the Filipinx-American and queer communities. These omitted histories of Black folk’s solidarity in our movements have made space for anti-Blackness in my communities, despite the foundational role they play in our freedom, rights, and efforts to combat white supremacy .

Stories of the iHotel: Chains That Unite Us

Although the resilience of my elders is not up for debate, to reduce the Filipinx-American community’s ability to take up space--both socially and politically--in America solely to the Filipinx-American experience is problematic. I wouldn’t be here without the work of Black folx too.

The International Hotel, or iHotel, was the site of a monumental civil rights battle between the city of San Francisco and the Filipinx-American community.

The hotel was an overseas home to hundreds of Filipino immigrant men in Historic Manilatown. When I think of the hotel’s residents, I think of my elders and the journeys they had to go through only to become underpaid and disenfranchised tools for cheap labor in the United States. The residents were forced to vacate due to the city’s plans to gentrify the neighborhood.

The Black Panther Party and their movement has consistently been cited by Filipinx activists as inspirations of early Filipinx activism movements. In 1977, Black folx and members of the Black Panther Party created human chains around the iHotel when the police came to forcibly evict the residents from their homes. They endured brutal force and beatings from officers on horseback who attempted to force through the crowds.

When hearing this story only a year ago, it made me feel immense pain after living a majority of my life being complicit and not speaking up for Black lives. I would do anything to protect my community, especially when I think of my elders, and watching footage of Black protestors outside of the iHotel being trampled by police for my community made me feel a deep sorrow for living a life where they were erased.

Black Trans Womxn and Queer Colonization

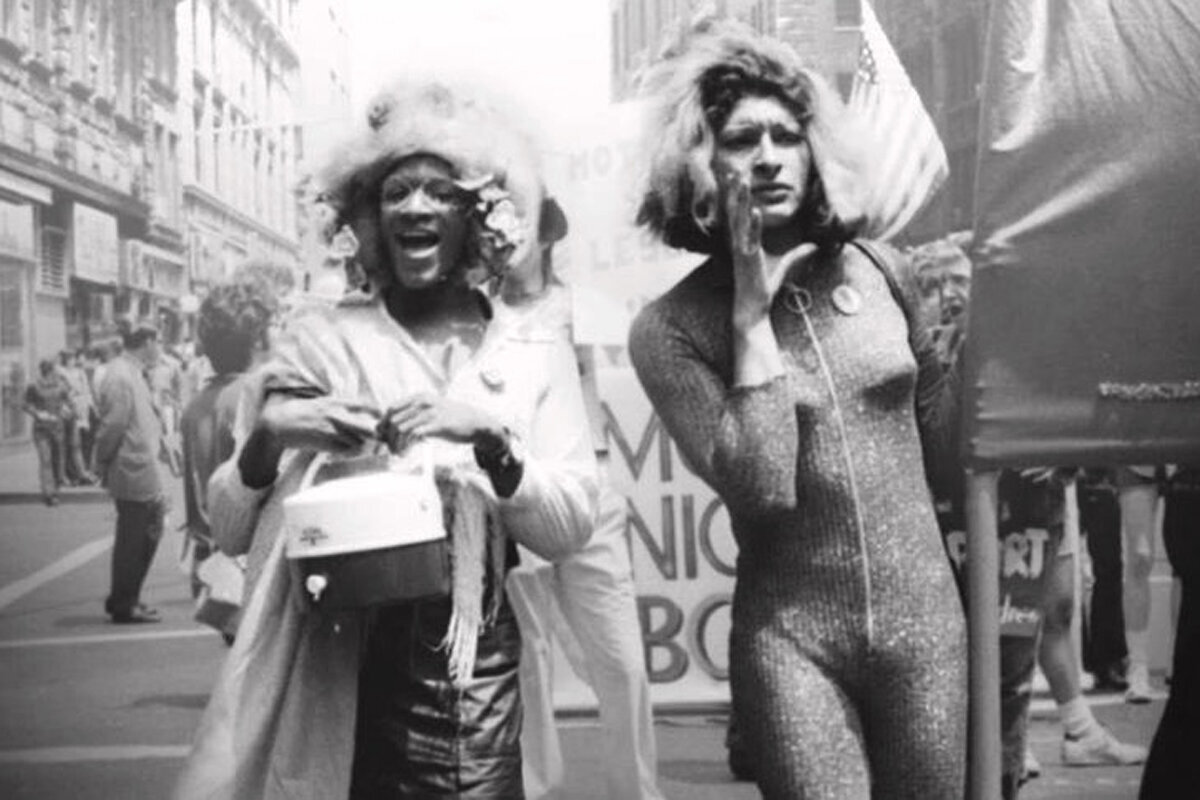

Black and transgender folx have historically been affected by violence from police, and fifty-one years ago a Black transgender womxn named Marsha P. Johnson began a revolution at the Stonewall Riots combatting the police for queer and trans rights in this country. She ignited a movement that made space for my existence as a queer Filipinx-American.

Marsha P. Johnson upheaved the very landscape of queer civil rights that I, and everyone within my community, enjoy to this day, and yet, I had never heard her mentioned in a history book. Instead, her legacy was colonized along with the community itself, overshadowed by white cisgender queer folx who became the face of the queer movement.

I wish I’d been educated sooner about Marsha P. Johnson, especially given her positionality as a non-white transgender Black womxn who pioneered my existence. While fighting for the community, she often entered leadership spaces within this movement that were made up of white folx. Having the knowledge of her willingness to fight for what she believed in, even if she didn’t fit the mold of the majority in our community, was something crucial I wish I had learned in the early formation of my queer Filipinx-American identity.

When we remove Black folx from our movement we create a culture of them as the “other,” we mimic the colonization of queer history. We ignore the Black community’s importance by centering ourselves and whiteness, which is potentially fatal as our solidarity with the Black community is crucial to combat the violence they’re facing from police and white supremacy itself.

The Culture And Effects Of Anti-Blackness

This sentiment of overshadowing Black folx is not isolated to just the LGBTQIA+ communities—Filipinx culture is anti-black.

Aleksa Manila, a legendary Seattle-based queer Filipinx-American drag queen and community organizer, believes solidarity against anti-Blackness is done through acknowledging our Philippine culture while listening to Black voices. This includes the issue of the skin whitening industry in the Philippines.

Manila highlighted how the Philippines’ beauty industry profits off the self-hatred of Filipinx peoples and their natural born skin, while further fueling the anti-Blackness that has permeated our culture from entertainment to our social behaviors.

“Heroes and heroines were always portrayed by light-skinned Filipino thespians, while villains were dark-skinned. Grab any magazine, and all the cover models are light-skinned with very obvious ads for skin bleaching products,” said Manila. “If you were a fan of any Philippine celebrity, you would see how lighter their skin became in just a few years.”

The erasure of Black folx from our histories and the anti-Blackness prevalent in our community creates a microaggressive culture. I can’t count how many times I’d hear titas at parties comment on how “pretty” light-skinned girls on television were but make comments on Black folx appearances, especially in regards to hair.

Living in this environment normalized this behavior, teaching me that darker skin is ugly, making me more prone to act microaggressively, and influencing me to celebrate whiteness. If our freedom and liberation is tied to combating white supremacy, how can we do that when we hate ourselves, our skin, and the Black community for our inabilities to conform to whiteness?

Unlearning And Going Beyond Performative Solidarity

After learning about Black-inclusive accounts of my queer Filipinx-American history, I wasn’t sure what to do. With much reflection, it occurred to me that I needed to take what I had been educated on and unlearn what this oppressive culture had taught me.

We must find both our commonalities and barriers, working collectively in understanding that our enemies are not each other.

Filipinx-American and Black leaders have done this throughout history, evident in the work done by Uncle Bob Santos and Larry Gossett from the Gang of Four. They were part of a coalition of four Black, Indigenous, Latinx, and Filipinx leaders who collectively fought for minority rights in Seattle from the early 60’s onward. They acted on the issues faced both within their own communities and throughout others.

Kalaya’an Mendoza, a Filipinx-American queer organizer and Direct-Action Trainer, sees the importance of this sentiment.

“You can’t consume Black culture and not give back to Black Liberation. That’s extractive and what a colonizer would do. Don’t be a colonizer,” Mendoza said. “We have a duty to fight against injustice. We need to center and uplift Black liberation because it means that we do the same for our people.”

Mendoza recently created a “_____ for Black Lives” graphic that has been widely shared on Asian-American’s social media. However, combating anti-Blackness goes beyond sharing a graphic.

Mendoza recommends avoiding “symbolic solidarity,” which can be done by unlearning, assessing your contributions to the oppression we see, and becoming an active ally through listening to the community.

“Let’s move past and through [symbolic solidarity] to end at transformative solidarity where we are leveraging our resources and privilege on a large scale to fight for equity for all people even at the cost of us benefiting from maintaining the status quo,” Mendoza said.

Transformative solidarity for Filipinos in 1977 in San Francisco meant that Black folk wouldn't allow struggling Filipinx-Americans to be evicted from the only place they could call home. And today, it looks like using our economic and social power to amplify the needs of the Black community.

“Listen to Black peoples, the Black Lives Matter Movement, their demands for social justice and to what ‘defund the police’ really means,” said Manila. “Look at your personal history followed by your family tradition and community culture of anti-Blackness. Understand where it’s stemming from.”

I came out in 2011 when I was thirteen, and although I faced a multitude of barriers in doing so, it would’ve been even more grueling of an experience without Marsha P. Johnson. I am constantly inspired in my work as a queer activist and journalist by trailblazing Black womxn, especially Marsha P. Johnson, who seemingly had the weight of all her communities on her shoulders yet effortlessly fought for them—a goal I envision for myself with my communities.

I cannot take back the eighteen years of my life where I lived by Black-omitted histories or problematically waited for Black folx to give me a reason to address anti-Blackness within my communities. What I can do is begin to unlearn previous notions of my identity and how my identity was formed, take action when noting disparities, and promote and live by anti-racism within these spaces.

If Black folx are dying and displaced, the shackles of white supremacy remain and liberation is halted. Liberation simply cannot exist when our Black communities are disproportionately being imprisoned, lost at the hands of the police, and met with violence and no justice.

Without the Black community’s work for civil rights and their allyship with my elders, I can’t imagine the community of Filipinx folx I have in San Francisco would be what it is. In a country upheld by white supremacy, Black folx inspire me to combat it in any way I can, the same way they have done so with my elders decades ago.

* * *

Andre Menchavez is a Filipinx queer activist and journalist based in Seattle, WA. He is pursuing a B.A. in Law, Societies, and Justice with a double minor in English and Diversity at the University of Washington. He also works as the Opinion Editor at the university’s newspaper, The Daily, while holding the title of Lead Junior Editor at GLAAD, a national non-profit LGBTQ media organization. You can read more of his work here, and follow his journey on Instagram!

Co-Editor: Kristine de los Santos, Director of Operations | One Down | kristine@one-down.com

Co-Editor: Leo Albea is the Creative Director of One Down and has worked with Beatrock Music on several occasions, including social videos for Rocky Rivera and Klassy, and most recently, as Director for Klassy’s Power Trip featuring Ruby Ibarra. For inquiries, he can be reached at leo@one-down.com. Follow him on Instagram!

* * *

Hi there, thanks for reading our latest story. Do you like this type of content? We’d love your support!

Since 2018, we’ve made it our mission to create a platform to cover every story that makes up what it means to be Filipino, and we need your support to continue this. Check out our fundraising campaign, which includes our newest ‘Filipinotown’ shirts, now available on our website: CLICK HERE